- Home

- Johnny Weir

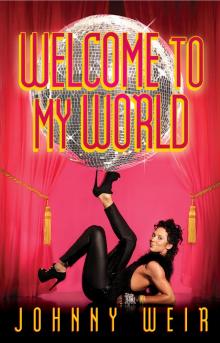

Welcome to My World Page 3

Welcome to My World Read online

Page 3

“Are you sure?” my mom asked because she’d say “Are you sure?” about everything. “Are you sure, Johnny?”

We were both crying by this point.

“Yes, Mom. I’m going to be a skater.”

In the spring of 1996, after only about ten months of living in Little Britain, my family packed up again to move to Delaware. Other than the trauma of my having to say good-bye to my pony Shadow, none of us shed too many tears about leaving the house in the middle of nowhere.

My extended family, however, was pretty shocked and upset. A number of them came down hard on my parents about moving not once but twice for the fancy dreams of a kid who hadn’t even hit puberty. “What the hell are you thinking?” one aunt said. “Why are you leaving Pennsylvania, everything you know, and your big beautiful house to move to a shit box in Delaware? It’s a cesspool down there.”

But my parents didn’t listen to any of it. As kids, both of them had a lot of dreams smashed before they could even start—whether because of strict parents, too many kids in the house and not enough money, or simple small-mindedness. They never wanted to regret having said no, so they did everything within their power to help me achieve whatever fantastical notion I set for myself.

I had to agree with my extended family on one point: our new house was kind of a shit box. At least compared to what we were used to back home. No more rolling hills, cornfields, forests, or quiet cul-de-sacs. Now we looked right into our neighbors’ windows and it really creeped me out. I kept my blinds shut tightly at all times; I’ve always put a high premium on privacy.

Luckily, there wasn’t too much time to dwell on Delaware and its shortcomings because I got swept up immediately in the ice rink. During that first summer program, I spent almost all day at the arena, five days a week, without ever stepping outside, even though the arena wasn’t more than eight minutes from our house by car.

My parents and I got up at four o’clock in the morning, early enough for them to drop me off and get to work at the power plant in Pennsylvania on time. By five o’clock I was out on the ice training with Priscilla. Because she didn’t want me to acquire bad habits, I wasn’t allowed to skate without her supervision. So by seven o’clock I was off the ice with about ten hours to kill before I could get back on the ice at five for one last hour of practice.

The rink—where I ate my packed lunch from home at a makeshift table using one of the chairs from an administrator’s office and took naps on a stretching mat in an open area above the stands—became my babysitter.

Because Priscilla had decided I would do pairs skating, as well as skate on my own, I had to do weight training in order to become strong enough to lift my partner. The trainer at the rink had his work cut out for him: I was a tiny, skinny kid for the longest time. At four foot nine and seventy pounds, people used to ask my mom all the time if she was feeding me.

I was fine with the weight training, but I really hated the dance classes that were also part of the summer program. There were five different teachers, one for every day of the week, including the un-jazziest jazz teacher on Mondays and a fat lady who taught modern dance Thursdays, and I despised all of them for boring me—except for Yuri on Wednesdays.

Originally from Saint Petersburg, Yuri Sergeev had danced with the Kirov Ballet and had a strange accent not unlike my idol Oksana. While he taught us Russian, Greek, and Moldovan folk dances, I had the same thrill as when I used to trace the Cyrillic alphabet from my book on the Soviet Union. Except that Yuri was alive and able to return my excitement.

He took me under his wing, offering me ten extra minutes after class to privately coach how to hold my arms or head in ways that would look good on the ice. I was built in a way that Russians favored when looking for kids to train as skaters, so Yuri knew the best positions for my body, and I loved the extra attention.

For the most part, though, I spent my time watching other kids practice and train. Seeing the skaters at the junior and senior levels go through their programs, get tangled in frustration, and work it out with their coaches was my greatest lesson during that period. I began to differentiate the styles from little clues like a straightened arm or tilt of the head. I was a sponge drinking up anything and everything that would make me a better skater.

The ice rink was a haven where I made friends who were equally passionate about skating and so made me feel comfortable expressing myself through music and movement. It stood in stark contrast to life outside, which was foreign, and not in a good way. Living in a new state, my parents, brother, and I were away from all our friends and family in what seemed like a big city filled with traffic lights, noise, and dirt.

As the temperature outside the rink dipped with the arrival of fall, I faced yet another terrifying aspect of my new life: school. I showed up the first day totally unprepared for the experience of eight hundred kids in an unruly urban middle school. My first mistake was my outfit. A small, pale kid, all eyes and lashes, I had chosen to wear jeans that hit a little above my ankle and a big, brightly colored polo shirt and my backpack with the straps on both shoulders. It’s like I wanted to be killed.

I couldn’t believe my eyes. Rocking big baggy jeans and ripped apparel were kids, if that’s what you could call them, in all colors and sizes. There were Asians and Jews, Muslims in head scarves and lots of African Americans. I had never been so close to black people and now they were knocking into me, big boys with as much facial hair as my dad.

It didn’t take long for the other students to find out that I was a skater—I only went to school half days to accommodate my training schedule—and begin calling me a “homo” or “faggot” when I walked down the hallway. They would sing aggressively anti-Johnny raps. But I was always strong enough to take that sort of thing. Especially now that I had skating to wrap myself in: it was my art and nobody could take it from me.

“So where did your son skate before this,” one of the other mothers asked my mom at the rink.

I was working on my double jumps, rotating twice in the air and coming down with a haughty flourish I’d developed with Yuri. Priscilla was yelling at me to stop jumping around and concentrate on my footwork. All I wanted to do was jump and have the arena whirling around me. I didn’t care at all about technique, but Priscilla beat it into me. She discovered my inner talents, the edge quality I became known for, and forced them out.

“This is the first place Johnny’s skated at,” my mom answered. “He’s only been skating for six months.”

“No way; he’s too good,” another mom said. “You have to be lying.”

Nobody believed my mother, Priscilla, or me that I had just started because I could already do a lot of the spins and jumps that the older kids were struggling with. I could do them without thinking, while they were falling and falling and falling. On the ice, it was clear that I had something special, but the other parents gossiped that I was keeping a secret. My mom hated it, but I love it when people talk about me.

I never wanted to do something that I was going to be mediocre at, even as a kid. So if I wasn’t a star, I would still pretend I was one. But when Priscilla would talk about me (“Oh, I have this wonderful boy I’m training”) or I would notice the other coaches coming to watch me while I practiced, I knew it wasn’t all in my head.

But I still had to prove myself in competition. My first big trial was the qualifying competition for the Junior National Championships in Pittsburgh. My training up to that point had been fast and furious to the point of dizzying. In order to get to the qualifiers that September, I had less than three months to pass a total of eight tests required by the U.S. Figure Skating Association (USFSA) for competing on an official level. I had already participated in a bunch of small, local competitions to get ready for battle. Although I had always won these contests by a landslide, I didn’t know how I would do on a much larger stage.

At my rink and even in the local competitions, I was in a safe nest where I was coddled by all the coaches and the ot

her kids around me. Because I was one of the only boys in my age group, everyone rooted for me to keep pushing. If I learned a new jump or new program, they told me how great it was. But would I skate as well surrounded by an arena full of strangers?

When we all piled into the car to make the drive from Delaware to Pittsburgh, the cool fall air smelled faintly of burning leaves. My skating partner Jodi Rudden and I had worn coordinated orange (me) and red (her) turtlenecks in homage to the season. She and I were similarly opinionated, driven, and outspoken, and we even looked alike with our pale skin, dark hair, and tiny bodies. The matching turtlenecks drove home the effect. In the car with my mom and Jodi’s mom, Janice, we were bouncing off the walls. It was the first time that I’d really been away. I couldn’t wait to stay in a hotel and eat in restaurants like a real grown-up.

Pulling up to the arena, the number of kids who had come to Pittsburgh to compete was bewildering. The South Atlantic region we were part of extended from Pennsylvania all the way down to Florida. I was up against twenty-two boys in my division of the singles skate, more than double the number of any of my previous competitions. Plus, the South Atlantic region has always been known as the strongest, the hardest, and the most talented group on the East Coast. Scanning the boys in my group, many of whom had the shoulders of miniature linebackers, I suddenly found the prospect of eating at T.G.I. Friday’s not all that appealing.

I competed in singles first. The rink was smaller than the University of Delaware’s arena, but family and skating fans packed the stands because my group, juvenile boys, were young and cute, a real crowd pleaser. We were divided into groups of six and thanks to the Weir family luck, which is not good, I drew to skate last in the last group. Waiting for boy after boy to complete his program, listening to the thunderous applause or, horror, the gasps of falls, proved utter torture.

By the time my group got on the ice for our six-minute warm-up period, I felt sick to my stomach. Those minutes ticked by as slowly as a century, but when they were over I made a beeline, still wearing my skates, for the lobby. Standing in my costume, I found my mom and said, “I want ice cream.”

I don’t know if I thought I was on death row ordering my last meal, or if the dairy would soothe my bubbling stomach, but I just needed something to calm me down. My mom rushed and got me a vanilla cone from a nearby stand that wasn’t doing too much business. I took a few licks and stoically returned to the rink.

Priscilla, who had traded her snowsuit for a big fur coat in honor of the event, guided me to the ice. I had gone about six shades paler than my already translucent skin. I felt awful. Why did I want to do this in the first place? I am a horrible person for selling Shadow and now I am going to pay. I’m not ready. What was Priscilla thinking, sending me out after only six months of training? A piercing shriek from the crowd broke my spiraling thoughts.

“Go, Johnny!”

It was my partner, Jodi. I looked up and saw her in her red turtleneck screaming for me. A whole group of people that I trained with—all the big kids and their parents—surrounded her. They pumped their fists and made catcalls.

Then my music started, and I did the only thing I could do: I went out and skated. After a whirlwind of jumps, spins, and footwork, I had earned all first place scores from the judges. Not too long after, Jodi and I killed in pairs, earning all first place votes, too.

We qualified for the Junior National Championships, which would be even harder than this competition and require a lot of training between then and April to be prepared. But more astounding than qualifying was the realization that, yes, I was as good as everyone said I was. It wasn’t all in my head. I floated home on the assumption that my entire future would come just as easily and naturally, but I was in for a rude awakening.

3

A Star Is Born

I sized up the other boys on the ice and thought, I’ve got this locked up. Not knowing what to expect at the Junior National Championships, I initially approached the biggest contest of my life so far with a fair share of trepidation. But during the practice right before the competition, I figured out that no one else could do a triple jump. In the five months since the qualifying championships in Pittsburgh, I had learned two different ones and had incorporated both into my program. A boy to my left landed with a thud during a double axel. Oh, yeah, I had this.

So far the trip out to Anaheim, California, had been a fantasy come to life. My partner, Jodi, and I traveled together—we were also competing in the pairs—and because it was spring and the West Coast, we ditched the turtlenecks for matching shirts: purple, the color of royalty. On my first long flight, I played a Wheel of Fortune video game my mom had bought me. This was heaven.

Bright, beautiful California felt like a different planet from dour Delaware. The sun shined all the time and people sold tropical fruit on the side of the road. Our hotel was big and comfortable, just how I like them. Young skaters from all over the country filled the elevators, rushed through the lobby, and caught up with old friends in the lounge. Because I was very shy, I didn’t make it a point to mix with the rest of the skaters but I shared in the excitement of our common goal.

During the warm-up, I felt extremely confident. But just like in my old bedroom, when my happy impressions would flip once the sun went down, my peace of mind vanished in the moments before the competition. As I waited for the announcer to call my name, my previously positive assessment of my chances of winning turned on its head. Suddenly I became convinced that I wouldn’t win. This was the first time I was performing the triple jumps in front of people at a competition. The best skaters in the world fell while doing them on TV all the time, and I hadn’t even been skating a year yet. Everything that had given me confidence became negative.

I couldn’t turn the worrying thoughts off. I knew they were my nerves flaring up and assumed they would sort themselves out once I settled into my program. But they followed me onto the ice and flew alongside me like harpies while I skated. I had grown a couple of inches in the last several months and my long legs suddenly felt as if they belonged to someone else.

The real problem, though, was my head. During my program, I made five or six mistakes and finished up with a curious mix of bewilderment, anger, and fear. However, nothing could prepare me for the shock about to come. When the judges presented their placements, there were all these different numbers I had never seen before: 14, 5, 6, 2, 13. I was used to seeing all ones. “What does this mean?” I asked. Well, what it meant was that I placed fourth in the men’s competition when I should have won it and experienced my first major loss. I was shocked. Even though I had been nervous, I hadn’t imagined not winning. I’d never truly contemplated failure.

Forget Jodi. Panic was my most trusted companion for the next two years as I went from a kid to an Olympic-level athlete. After my first taste of losing at the National Championships, I discovered another part of myself that couldn’t be controlled simply with hard work and talent. I was never sure who would show up on competition day—confident Johnny or the guy who choked. Just like the vivid thoughts in my head as a child that made my environment delightful during the day and conversely paralyzed me at night, the force of my personality worked both for and against me.

Very often I did well. After moving from juvenile up two levels to novice, I won the regional and sectional championships and then placed third in the National Championships in 1998. Right after turning fourteen, I won a Junior Grand Prix event in Slovakia, beating a lot of high-level junior skaters who were older than me.

But just as often, I didn’t do well. In 1999, the year I learned to do a triple axel, the jump necessary to compete at the Olympic level, I completely psyched myself out during my first competition of the Junior Grand Prix in the Czech Republic and suffered a humiliating defeat, coming in seventh.

I was all over the place. On the one hand, I decided I wanted to go to the 2002 Olympics in Salt Lake City, Utah. I knew I wouldn’t be a champion, but I thought I could m

ake the team after only five years of skating, which was ludicrous. On the other, I was completely out of my comfort zone while competing. It didn’t matter that I trained every single day, going through the exact same routine perfectly without problems. As soon as I stepped on the ice for a competition, I started sweating and my heart raced. Every imaginable bad thought worked its way into my head: you’re ugly, you’re lazy, you’re just not good enough. I was my harshest critic.

My big problem—one that stayed with me for a long time in my career—was that I didn’t know how to compete. Unlike most kids who start on the ice at three years old, getting their makeup done, wearing costumes, and learning to compete against other kids, I went right from zero to national-level competition. I didn’t get that comfortable kiddie period to learn how to react in different situations, how to deal with stress, and, most important, how to keep nerves under control. Going from zero to sixty, I was crashing left and right.

I was also becoming a teenager. What a combo. When you’re an angst-ridden hormonal mess, that’s a wonderful time to undergo constant scrutiny.

As I started to grow hair in places where I didn’t think people should have hair, I sprang up from my long-standing height of four foot nine to five six while barely tipping the scales at a little over one hundred pounds. I was still a beanpole, but a bigger beanpole. With my body changing, I not only had to deal with normal anxieties but also keep adjusting my techniques.

By the 2000 National Championships, I had a full-on career crisis at the ripe old age of fifteen. Even though I fell on my triple axel in the short program, none of the other skaters tried one, so the judges still put me in first. But then, with the expectation of winning that I found crippling, I had a complete meltdown in the free program. Obsessed with trying not to fall, of course I fell. It was my first competition against Evan Lysacek, a then skinny waif from Illinois. Until my debacle during the free program, Evan had been in fifth place. Ultimately he won and I took fifth.

Welcome to My World

Welcome to My World